Defining goals, objectives, and hypotheses

Conducting user research takes a significant amount of preparation before you even begin asking users anything. However, the time you spend creating alignment and developing a research plan pays off tremendously because it keeps you on track as you carry out your research.

Starting with a good question and the right question will ensure you end up with a useful answer. A good research question is specific, actionable, and practical. That means:

- It’s possible to answer the question using the techniques and methods available to you.

- It’s possible but not guaranteed that you can arrive at an answer with a sufficient degree of confidence to base decisions on what you’ve learned.

Only after you have identified your research question(s) can you select the best way to answer the question (for example, which research method to use).

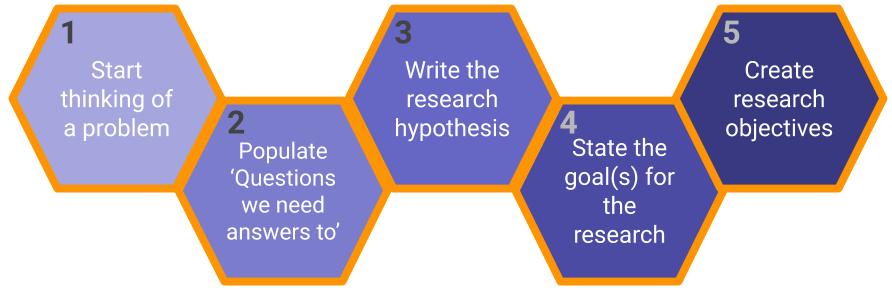

As the figure below shows, there are 5 main steps to creating research hypothesis, goals, and objectives.

Step 1 - Start thinking of a problem

When you hear a customer problem, it can be tempting to just dive right in and devise a solution. However, it’s important to remember there is never just one good solution to a problem. A problem can be solved in many different ways, depending on what we need to focus on.

Users can also be unpredictable. What we think might solve their pain points may not actually even begin to address the problems they are facing. Therefore, it’s advisable to test your ideas before you start building a solution. A way in which you can do this is to write and test hypotheses.

What is a hypothesis?

A hypothesis is basically an assumption. It’s a statement about what you believe to be true today. It can be proven or disproven using research.

A strong hypothesis is usually driven by existing evidence. Ask yourself: Why do you believe your assumption to be true? Perhaps your hunch was sparked by a passing conversation with a customer, something you read in a support ticket or issue, or even something you spotted in GitLab’s usage data.

- Ask yourself:

- What current beliefs do you have about the user?

- What organizational or other barriers do you need to be mindful of?

- What are the business objectives for the project?

- What questions does the research need to answer?

- What are we trying to learn?

- What must the research achieve?

- Does any prior research exist?

- What did prior research tell us?

| Start thinking of a problem | Questions we need answers to | Hypothesis | Goal | Objectives |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Let’s imagine that a hotel chain has noticed they have had a lower number of bookings in the last few quarters, but they are unsure why. |

Step 2 - Start populating ‘Questions we need answers to’

- This is meant to be a brain dump of all the answers you came up with from step 1.

- These aren’t the questions you’ll directly ask users - you’ll get to that step later as you fill out your discussion guide.

| Start thinking of a problem | Questions we need answers to | Hypothesis | Goal | Objectives |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Let’s imagine that a hotel chain has noticed they have had a lower number of bookings in the last few quarters, but they are unsure why. |

|

Step 3 - Fill out the hypothesis

- Use the questions you listed in step 2 to guide you.

How to structure a hypothesis

There are lots of different structures for hypotheses, but a good approach is to use this simple statement:

We believe [doing this] for [these people] will achieve [this outcome].

The statement consists of three elements.

We believe [doing this]should detail your proposed solution to users’ problems.for [these people]should identify who you are targeting.will achieve [this outcome]is where you should document your measure of success. What is your expected result?

For example:

| Start thinking of a problem | Questions we need answers to | Hypothesis | Goal | Objectives |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Let’s imagine that a hotel chain has noticed they have had a lower number of bookings in the last few quarters, but they are unsure why. |

|

We believe that by improving the experience of selecting and deciding which of our hotels to stay at for users of our website will achieve in an increased number of hotel bookings. |

When writing your hypothesis, focus on simple solutions first and keep the scope small. If you’re struggling to articulate your assumptions about users, it’s probably better to start with developing a better understanding of users first, rather than forming weak hypotheses and running aimless research studies.

Step 4 - State the goal(s) for the research

- Goals need to be specific enough so you’ll know when you’ve reached an answer, practical in that you could answer them within the scope of a study, and actionable in that you could act on your findings once you’ve completed your research study.

- The goal is the central question that has to be answered by the research findings.

- Always start goals using a verb such as identify, understand, learn, gauge, etc.

- Limit the number of goals you define per project. Try to learn one or two things very well. This will help you connect your research to a design outcome and emerge with a clear understanding of one aspect of user behavior.

| Start thinking of a problem | Questions we need answers to | Hypothesis | Goal | Objectives |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Let’s imagine that a hotel chain has noticed they have had a lower number of bookings in the last few quarters, but they are unsure why. |

|

We believe that by improving the experience of selecting and deciding which of our hotels to stay at for users of our website will achieve in an increased number of hotel bookings. |

Understand how people make their travel plans. |

Step 5 - Create research objectives

- A well written list of research objectives:

- Delineate and align with the goal of the project.

- Define the overall high-level approach and the questions you might ask.

- Dictate the most suitable methods and tools at your disposal.

- Determine the outcomes you will get from the study.

- Need to be high level, but specific enough that research can provide a concise answer for each.

- Create no more than 4 objectives per research effort. If you try to achieve more than 4 objectives in one study, you are doing too much, as each objective will represent up to a dozen questions/tasks in your discussion guide.

- Review the list of the ‘Questions we need answers to’ and identify the themes you see there. Reference the ‘Hypothesis’ and the ‘Goal(s)’ you have previously written.

| Start thinking of a problem | Questions we need answers to | Hypothesis | Goal | Objectives |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Let’s imagine that a hotel chain has noticed they have had a lower number of bookings in the last few quarters, but they are unsure why. |

|

We believe that by improving the experience of selecting and deciding which of our hotels to stay at for users of our website will achieve in an increased number of hotel bookings. |

Understand how people make their travel plans. |

|

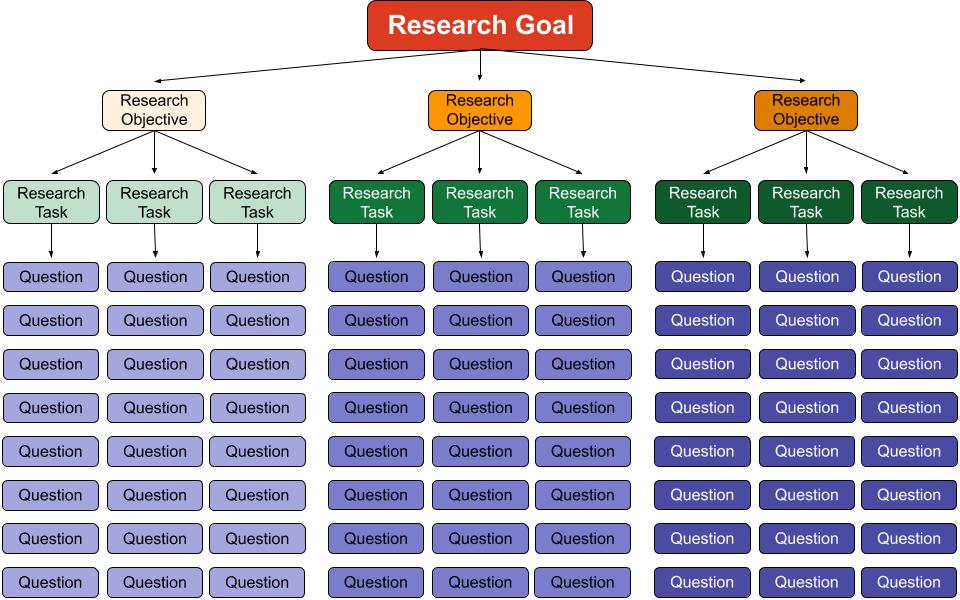

The chart below shows the relationship between your research goal and the tasks and questions you will ask your participants in usability tests.

This chart shows the relationship between your research goal and the interview questions you will ask your participants in user interviews.

As you can see, the more objectives you start out with, the more questions you will need to ask and the longer your research session will be. It’s a good rule of thumb to not have the user session last longer than 1 hour. Our typical research sessions at GitLab last 30-45 minutes.

Test your hypothesis

A good user research project creates conditions where you can see if your hypothesis seems to be true or false by evaluating both performance and attitudinal data. A simple binary metric (yes/no, pass/fail, etc.) is used to gather performance data. Attitudinal data, such as sentiments and opinions, helps you to describe your participants’ experience.

A strong hypothesis is easy to test. It shouldn’t take you much time to design a research study to validate or invalidate your hypothesis.

If your hypothesis is invalidated by users, don’t feel disheartened. You’ve stopped precious Engineering time being spent on building a solution that simply doesn’t solve users’ problems. A good measure of being iterative is throwing something away because user research proved that it wasn’t going to work. You’re not always going to get things right the first time. We learn more about user needs as a result of testing multiple hypotheses and, in turn, we generate new ideas for future rounds of testing.

9b1952da)